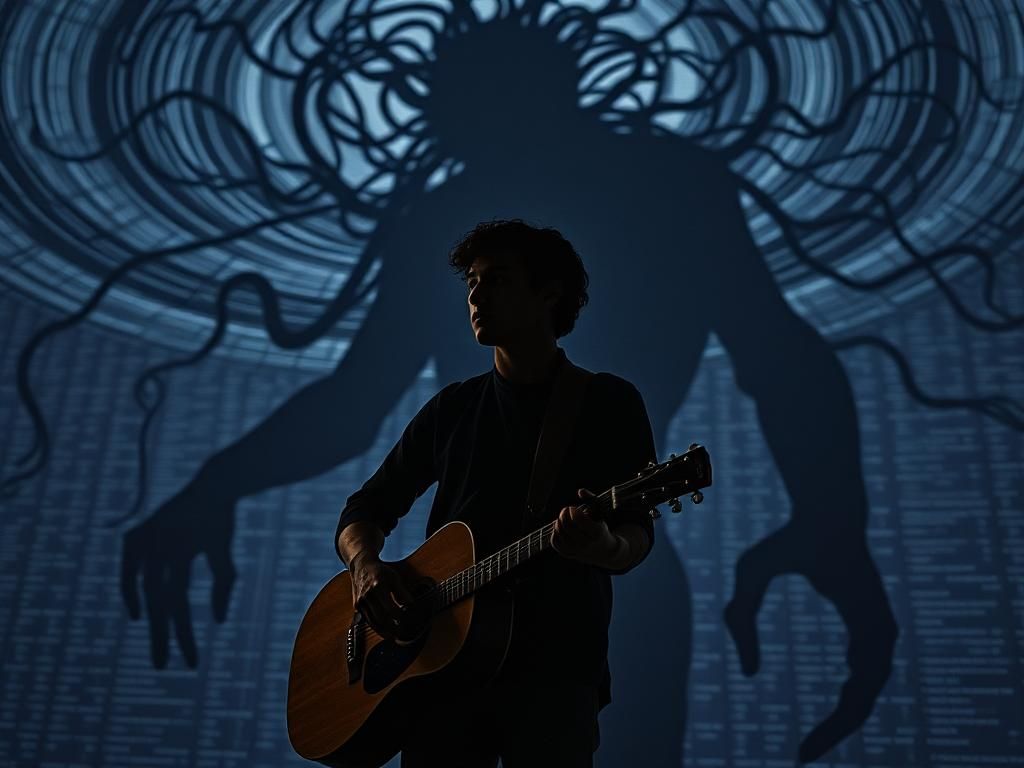

The recent sensation surrounding Velvet Sundown captured global attention, sparking intense debate across the music and media landscapes. Was it a groundbreaking musical phenomenon, a clever marketing ruse, or merely a stark preview of an already unfolding reality? The enigmatic breakout act garnered hundreds of thousands of streams, captivating audiences before allegations surfaced that the band and its distinct sound were entirely products of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI). While the “band” initially maintained its authenticity, a subsequent admission from an “associate” confirmed it as an elaborate “art hoax” and marketing stunt. Much of the ensuing discourse gravitated towards issues of fairness, particularly the perception that a “fake” entity was achieving success at the potential expense of legitimate human artists. Yet, Velvet Sundown is far from an isolated incident; it represents merely the latest chapter in a rich, decades-long narrative of computer-generated and augmented music creation. This evolution poses profound questions for the music industry, especially in smaller markets like New Zealand, where artists already navigate unique challenges without adequate protective frameworks in place for the complexities introduced by AI.

The convergence of advanced AI capabilities with creative industries, particularly music, has created a complex web of opportunities and threats. While AI promises new avenues for artistic exploration and efficiency in production, it simultaneously introduces unprecedented challenges related to intellectual property, artist livelihoods, and cultural integrity. For New Zealand, a nation with a vibrant and distinct musical heritage, understanding and proactively addressing these shifts is paramount to safeguarding its creative future.

THE ECHOES OF INNOVATION: A BRIEF HISTORY OF AI IN MUSIC

The concept of machine-generated music is not a modern invention born of Silicon Valley. Its origins trace back to the mid-20th century, notably in 1956 when chemistry professor Lejaren Hiller unveiled the Illiac Suite for String Quartet, a musical composition meticulously crafted by a computer. This pioneering work laid the groundwork for future experiments. Decades later, in the 1980s, David Cope’s ambitious Experiments in Musical Intelligence (EMI) pushed boundaries further, creating music so stylistically indistinguishable from the works of masters like Chopin and Bach that it successfully deceived classically trained musicians.

More recently, the discourse shifted from mere algorithmic composition to the ethical implications of voice synthesis and deepfakes. Artist and composer Holly Herndon was a vocal advocate for the ethical application and licensing of voice models and deepfake technologies years before figures like Grimes openly invited others to use AI-generated versions of her voice to produce new music. The emergence of “Deepfake Drake,” an AI-generated collaboration that mimicked the voices of Drake and The Weeknd, sent ripples of alarm through major record labels, highlighting the immediate commercial and legal challenges.

The music industry’s embrace of AI extends beyond mere experimentation. Major companies, including Warner and Capitol Records, alongside influential figures like rapper-producer Timbaland, have inked contracts with AI-generated acts and platforms. Furthermore, AI-powered tools have seamlessly integrated into standard music production workflows. Software from Izotope and LANDR, along with features in Apple’s Logic Pro, leverage machine learning for mixing and mastering, becoming indispensable tools for many producers since the late 2000s. Even the ubiquitous streaming recommendations that shape listener habits are underpinned by sophisticated machine learning algorithms. For artists exploring new creative avenues, accessible AI tools, such as a free AI audio generator, offer exciting possibilities for prototyping sounds or generating instrumental tracks, further democratizing aspects of music production.

THE NEW ZEALAND CONTEXT: A PIVOTAL MOMENT

Despite this extensive history of technological influence on music, the current wave of AI disruption is frequently framed as an impending future challenge rather than a present reality. The New Zealand government’s Strategy for Artificial Intelligence, unveiled recently, characterizes the present moment as “pivotal” as the AI-powered future rapidly materializes. This sentiment is echoed in recent initiatives from key cultural bodies.

In June, a draft insight briefing from Manatū Taonga/Ministry for Culture & Heritage delved into “how digital technologies may transform the ways New Zealanders create, share and protect stories in 2040 and beyond.” This forward-looking report joins other significant publications by the Australasian Performing Rights Association (APRA AMCOS) and New Zealand’s Artificial Intelligence Researchers Association, all of which are actively grappling with the multifaceted future impacts of AI technologies on the nation’s creative landscape. While these efforts acknowledge the looming shifts, the practical protections for local artists remain largely undefined, leaving a significant gap between strategic discussion and actionable legal frameworks.

UNPACKING THE CORE CHALLENGES: COPYRIGHT AND CREATIVITY AT STAKE

TRAINING DATA AND COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT

One of the most contentious issues at the heart of AI’s impact on music is the unconsented use of copyrighted material to train AI systems. Last year, two prominent AI startups, one of which was reportedly utilized in the Velvet Sundown phenomenon, faced lawsuits from music giants Sony, Universal, and Warner. The core of these legal challenges centered on the startups’ alleged use of unlicensed recordings as fundamental components of their training data. This raises a crucial question for Aotearoa: it is highly probable that these models have also ingested recordings by New Zealand musicians without their explicit permission. However, without any mandatory requirement for tech firms to disclose the datasets used for training, confirming such infringements remains virtually impossible, leaving local artists in a vulnerable position with little recourse.

UNCLEAR LEGAL LANDSCAPE FOR AI-GENERATED WORKS

Even if the origin of the training data could be ascertained, the legal ramifications for works generated by AI in Aotearoa New Zealand remain remarkably ambiguous. The existing copyright framework struggles to define ownership and rights when a creative work is primarily, or entirely, an output of an artificial intelligence. This lack of clarity creates a significant void, making it challenging for musicians to understand their rights, or even to effectively opt out their original works from being used as training data in any meaningful or enforceable way. The absence of clear guidelines places the onus of protection almost entirely on individual artists, who often lack the resources to navigate complex international legal battles against well-funded AI developers.

CULTURAL INTEGRITY AND MĀORI SOVEREIGNTY

Beyond general copyright concerns, the implications for cultural integrity are particularly acute in New Zealand. The data governance model championed by Te Mana Raraunga/Māori Sovereignty Network advocates for Indigenous data sovereignty and protection. Within the music sector, Māori writer members of APRA AMCOS have voiced significant concerns about the potential for cultural appropriation and misuse arising from GenAI technologies. Without robust safeguards, there is a risk that AI models, trained on vast datasets that may include Indigenous artistic expressions, could generate content that inadvertently, or deliberately, misrepresents, trivializes, or profits from Māori culture without proper attribution, consent, or benefit-sharing, undermining long-standing principles of kaitiakitanga (guardianship) over taonga (treasures).

ECONOMIC DISPLACEMENT AND ARTIST VISIBILITY

A recent study from Stanford Graduate School of Business suggests that GenAI-generated content has the potential to displace human output in various creative industries. This finding is particularly alarming for New Zealand musicians, who already face considerable hurdles in gaining visibility and achieving sustainable careers within a comparatively small domestic market. If AI-generated music floods streaming platforms and media channels, it could further marginalize human artists, making it even harder for them to break through the noise and connect with audiences. This economic threat is not isolated; in Australia, GenAI has reportedly been used to impersonate successful, emerging, and even deceased artists, complicating revenue distribution and intellectual property rights. Furthermore, French streaming service Deezer reported an astonishing 20,000 GenAI-created tracks being uploaded to its platform daily, illustrating the sheer volume of AI-generated content entering the market, potentially diluting the value and prominence of human-created art.

THE SHADOWS OF DEEPFAKES AND STREAMING FRAUD

THE RISE OF AI SLOP AND IMPERSONATION

The proliferation of AI has also led to an increase in illicit activities that directly undermine artists. There has been heightened scrutiny of streaming fraud, culminating in a world-first criminal case brought last year in the US against a musician who utilized bots to artificially inflate streaming numbers for GenAI-generated tracks into the millions. On social media platforms, musicians are now forced to contend for audience attention amidst a relentless deluge of what is colloquially termed “AI slop”—low-quality, mass-produced content. The troubling reality is that there appears to be little, if any, genuine prospect of major platforms implementing effective measures to curb this tide, leaving human creators at a significant disadvantage in terms of discoverability and engagement.

DEEPFAKE THREATS TO ARTIST IDENTITY AND LIVELIHOODS

Perhaps even more concerning is the burgeoning threat of deepfakes and non-consensual intimate imagery. New Zealand law has been widely described as “woefully inadequate” when it comes to combating these malicious uses of AI. The potential for deepfakes to damage artists’ brands, reputations, and livelihoods is immense. Imagine an artist’s voice or image being manipulated to create content they never endorsed, or worse, to generate non-consensual material. Such incidents can inflict irreparable harm, eroding public trust and causing profound personal and professional distress. The current legal framework provides insufficient recourse, leaving artists vulnerable to sophisticated digital abuses that threaten their very identities and careers.

GLOBAL CALLS FOR REGULATION: A BENCHMARK FOR AOTEAROA

In contrast to New Zealand’s relatively “light-touch” approach to AI regulation, which prioritizes adoption and innovation over cultural and creative protections, there is a growing international consensus that regulatory intervention is not merely warranted but essential. Other jurisdictions are taking decisive steps to address the challenges posed by AI, offering potential blueprints for Aotearoa.

THE EUROPEAN UNION’S PIONEERING AI ACT

The European Union has enacted landmark legislation with its AI Act, a comprehensive framework that mandates transparency for AI services. Crucially, it requires AI developers to disclose the data used to train their models. This transparency is a vital first step towards establishing a functional AI licensing regime for recorded and musical works, ensuring that artists and rights holders have a clear understanding of when and how their creations are being used and are adequately compensated.

AUSTRALIA’S COMPREHENSIVE AI GUARDRAILS

Across the Tasman, an Australian senate committee has recommended the implementation of “whole-of-economy AI guardrails,” which include transparency requirements that align closely with the EU’s proactive stance. This holistic approach signals a recognition that AI’s impact is pervasive and necessitates broad regulatory oversight, rather than piecemeal interventions, to safeguard various sectors including the creative industries.

DENMARK’S UNIQUE INDIVIDUAL COPYRIGHT APPROACH

Denmark has gone even further in its protective measures, proposing groundbreaking plans to grant every citizen copyright over their own facial features, voice, and body. This bold initiative includes specific, enhanced protections tailored for performing artists. Such a framework could provide a powerful legal shield against deepfakes and unauthorized AI reproductions of an artist’s unique identity and performance, offering a robust model for protecting individual creative sovereignty in the digital age.

NAVIGATING THE FUTURE: PROTECTING NZ’S MUSICAL HERITAGE

Nearly a decade ago, the music business was presciently described as the “canary in a coalmine” for other industries, serving as a reliable bellwether for broader cultural and economic shifts. Today, this metaphor rings truer than ever. The challenges currently presented by artificial intelligence within the music industry are not isolated phenomena; how nations choose to address them will have profound and far-reaching implications across all creative sectors and beyond. For New Zealand, a nation that prides itself on its innovative spirit and vibrant artistic community, the urgency of developing robust, artist-centric AI policies cannot be overstated.

It is imperative that New Zealand moves beyond a purely “light-touch” regulatory approach and embraces a comprehensive strategy that balances innovation with essential protections. This involves: establishing clear copyright frameworks for AI-generated works; mandating transparency regarding AI training data; providing meaningful opt-out mechanisms for artists; and, crucially, addressing the unique concerns around cultural appropriation and Māori data sovereignty. Learning from international precedents set by the EU, Australia, and Denmark, New Zealand has an opportunity to craft forward-thinking legislation that safeguards its artists, preserves its cultural heritage, and ensures that the future of music remains rooted in human creativity, even as it harnesses the power of artificial intelligence.